| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Parametrized policy | Neural networks are powerful and flexible function approximators, so we can represent a policy using a neural network with learnable parameters - this is the policy network . Each specific set of parameters of the policy network represents a particular policy - this means that for and a state , and a single policy network architecture is therefore capable of representing many different policies. |

| The objective to be maximized 1 | The expected discounted return, just like in MDP. |

| Policy Gradient | A method for updating the policy parameters . The policy gradient algorithm searches for a local maximum in : . This is the common gradient ascent algorithm that adjusts the parameters according to where is the learning rate. Note that we can pose the objective as a loss that we try to minimize by negating it. |

Log-Derivative TrickWe begin with a function and a parametrized distribution .

We want to compute the gradient of the expectation and rewrite it in a form suitable for Monte Carlo estimation.

Step-by-step derivation

Step 1: Definition of expectation

Step 1: Definition of expectation

Explanation:

This uses the definition of an expectation under a density:

Step 2: Leibniz rule

Step 2: Leibniz rule

Explanation:

Under mild regularity conditions, differentiation and integration commute (Leibniz rule), allowing us to move inside the integral.

Step 3: Product rule

Step 3: Product rule

Explanation:

This applies the product rule to .

Step 4: Simplification

Step 4: Simplification

Explanation:

We assume does not depend on , so and the second term vanishes. This is the standard situation in policy-gradient and score-function estimators.

Step 5: Multiply and divide

Step 5: Multiply and divide

Explanation:

Multiply and divide by ; this is valid whenever on the support of interest.

Step 6: Log-derivative identity

Step 6: Log-derivative identity

Explanation:

We use the log-derivative identity:

Step 7: Back to expectation form

Step 7: Back to expectation form

Explanation:

We rewrite the integral back into expectation form.

Algorithm: Monte Carlo Policy Gradient (REINFORCE)

| Line | Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | Initialize learning rate |

| 2 | Initialize policy parameters of policy network |

| 3 | for episode to MAX_EPISODE do |

| 4 | Sample trajectory using |

| 5 | |

| 6 | for to do |

| 7 | Compute return |

| 8 | |

| 9 | end for |

| 10 | |

| 11 | end for |

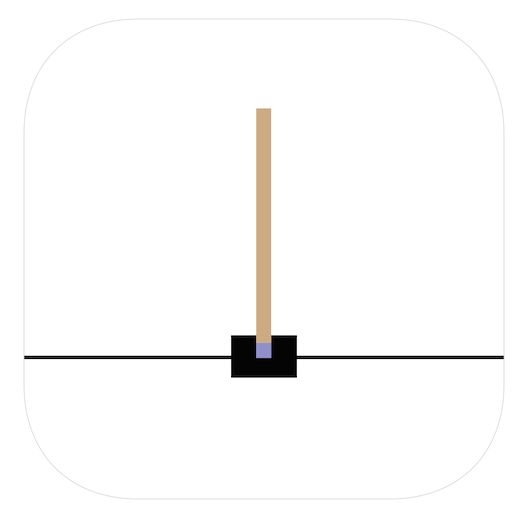

Policy Network

One of the key ingredients that REINFORCE introduces is the policy network that is approximated with a NN eg. a fully connected neural network (e.g. two RELU-layers). 1: Given a policy networknet, a Categorical (multinomial) distribution class, and a state

2: Compute the output pdparams = net(state)

3: Construct an instance of an action probability distribution pd = Categorical(logits=pdparams)

4: Use pd to sample an action, action = pd.sample()

5: Use pd and action to compute the action log probability, log_prob = pd.log_prob(action)

Other discrete distributions can be used and many actual libraries parametrize continuous distributions such as Gaussians.

Applying the REINFORCE algorithm

It is now instructive to see an stand-alone example in python for the so calledCartPole-v0 2

References

- Rafati, J., Noelle, D. (2019). Learning sparse representations in reinforcement learning.

- Schulman, J., Wolski, F., Dhariwal, P., Radford, A., Klimov, O. (2017). Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms.

- Schulman, J., Levine, S., Moritz, P., Jordan, M., Abbeel, P. (2015). Trust Region Policy Optimization.

- Szepesvári, C., Cochran, J., Cox, L., Keskinocak, P., Kharoufeh, J., et al. (2010). Reinforcement Learning Algorithms for MDPs. Wiley Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science.

- Wang, J., Kurth-Nelson, Z., Tirumala, D., Soyer, H., Leibo, J., et al. (2016). Learning to reinforcement learn.

Footnotes

- Notation wise, since we need to have a bit more flexibility in RL problems, we will use the symbol as the objective function. ↩

-

Please note that SLM-Lab, is the library that accompanies this book. You will learn a lot by reviewing the implementations under the

agents/algorithmsdirectory to get a feel of how RL problems are abstracted. ↩