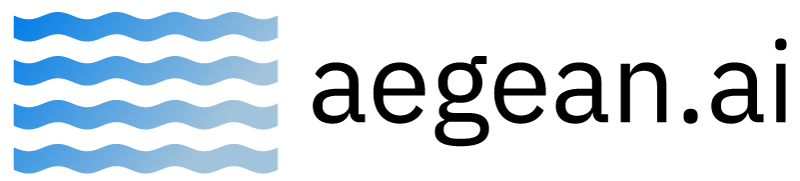

Agent-Environment Interface

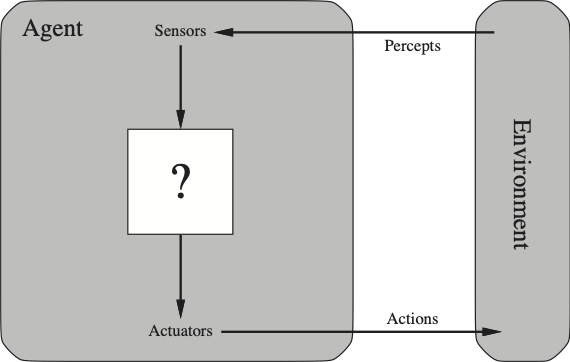

An agent is a computer system that is situated in some environment, and that is capable of autonomous action in this environment in order to meet its design objectives. In general sensor data are converted via the agent function (that is implemented via a program) into actions as shown below.

- Partially Observed (PO). This means that we cant see all the variables that constitute the state and we need to maintain an internal belief of the state variables that we cant perceive.

- Stochastic. This means that the environment state is affected by random events and can not be determined by the previous state and the actions of the agent (which in this case we are talking about deterministic environments). Such probabilistic characterization of the environment state is the norm in many settings such as as robotics, self-driving cars etc.

- Sequential As compared to episodic, in sequential environments actions now can have long term effects into the future.

- Dynamic In this setting, the environment state changes all the time, even while the agent is taking the action based on the sequence of percepts up to this point in time. In most settings the environments we deal will not be static.

- Continuous When the variables that constitute the environment state are defined in continuous domains. Time is usually considered a special variable and we may have environments where the time variable is discrete while other variables are continuous.

- Known This refers to the knowledge of the agent rather than the environment. In most instances we are dealing with environments where there is a set of known rules that govern the state transition. In driving for example, we know what steering does.

Architectures

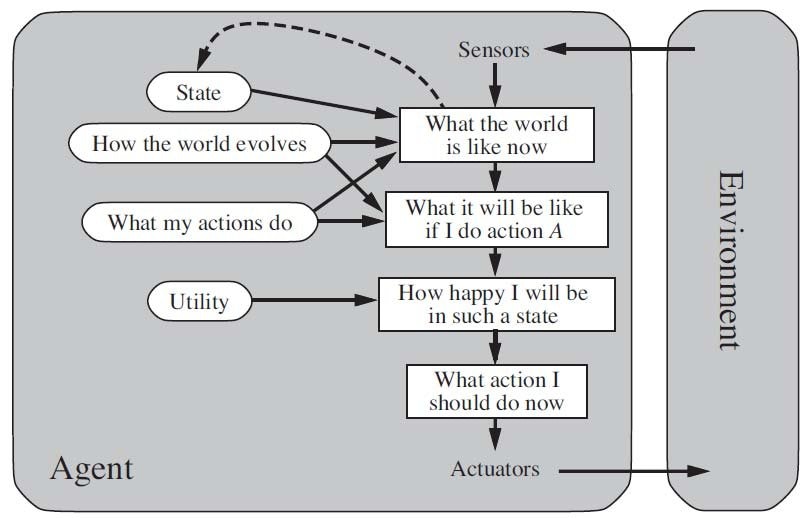

Rational Agent Architecture

- The need for the agent to keep internally the environment state (in probabilistic terms a belief). This is needed due to the the partially observed environment the agent is interfacing with.

- The presence of a world model that helps the agent to update its belief.

- The presence of a utility function that the agent can use to produce the value (happiness) when its action transitions the environment to a new state. Obvious the agent will try to optimize its actions in what we earlier described stochastic environments and therefore it will try to maximize the value (hapiness) on average (strictly in expectation) where the average is taken across the distribution of all possible states across time.

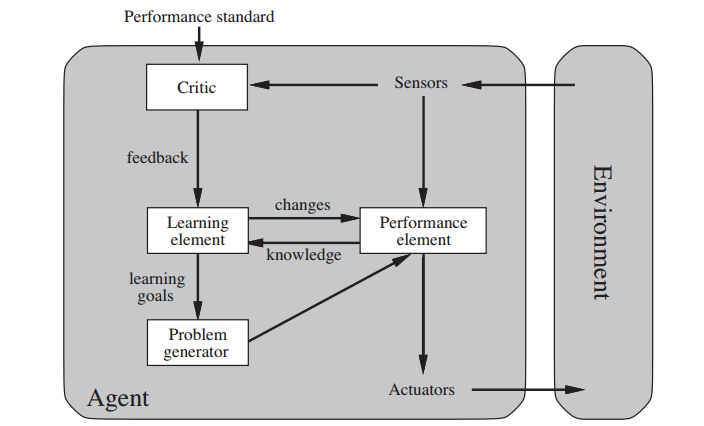

Learning Agent Architecture

- Embeds a learner that learns the various models needed by the rational agent as well as allowing the rational agent to operate on unknown environments. In this respect it learns the world model, some elements of the utility function itself or the desirability of each actions it takes. To enable learning, the rational agent sends training data to the learner.

- Introduces a critic that transmits a positive or negative reward to the learner based on its own view of how the agent is doing. The learner can modify these models to make the rational agent perform better in the future.

- Introduces the problem generator that can change the problem statement of the rational agent. Obviously the expected utility objective will not change but the utility function itself may in fact change to lead the agent to perform more exploration in its environment.

AI Agents in Robotics

Modern robotics demonstrates how these agent architectures translate into real-world systems. In the demo below, a robot follows instructions in natural language—the instructions are typed in this demo but spoken instructions are very much feasible today as well.

ROSA Demo: Robots can follow natural language instructions - Video developed by Oscar Poudel as part of the “AI for Robotics” Spring 2025 class project.

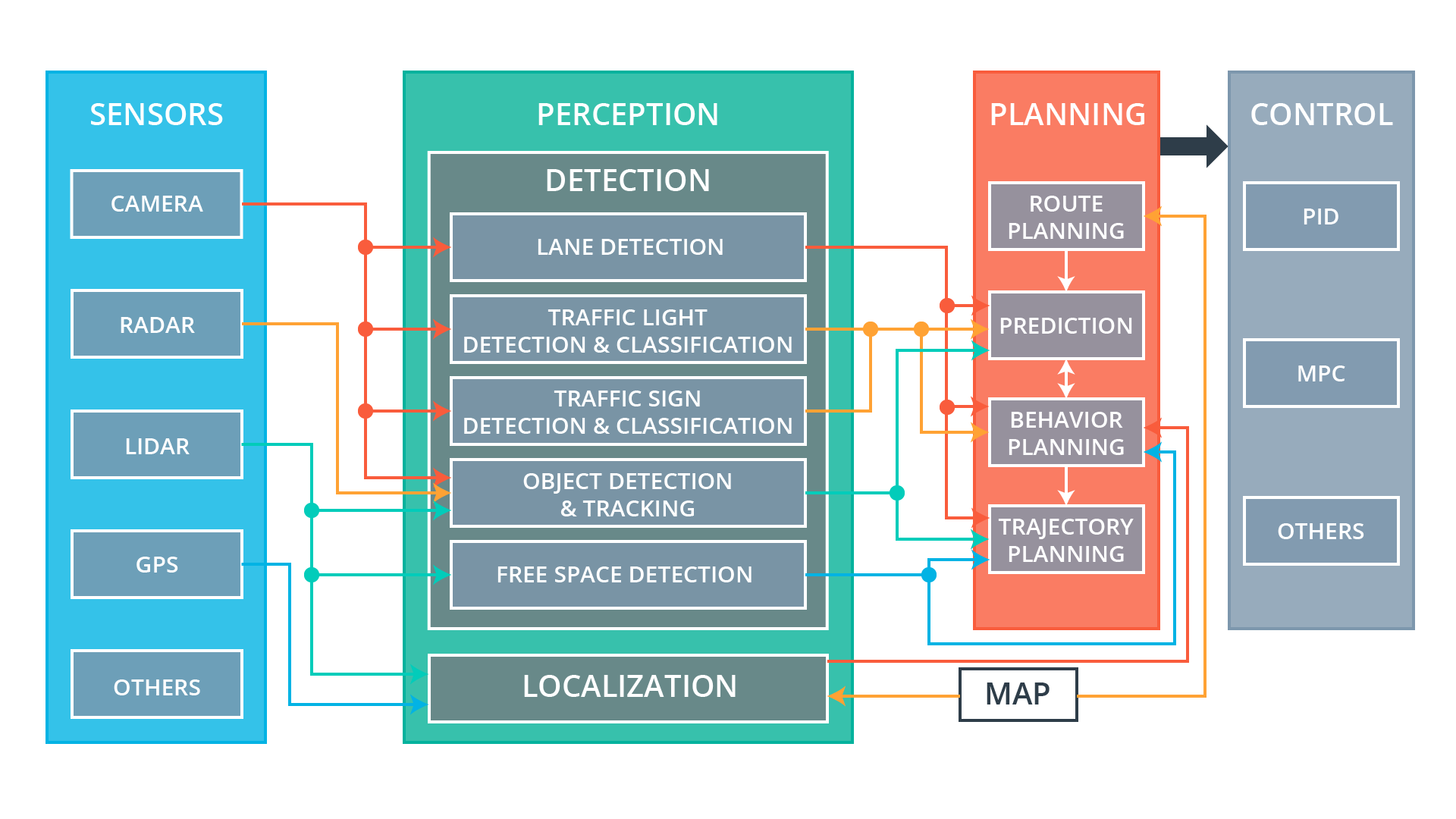

In 2023 OpenAI released ChatGPT, a large language model (LLM) that can understand and generate human-like text. This breakthrough has led to a surge in interest in AI applications across various fields, including robotics. Today’s robotics landscape is still exhibiting the aftermath of the Large Language Modeling (LLM) revolution. To understand how pervasive the impact is, it’s important to turn the clock back and look at a traditional autonomous vehicle architecture that is still considered state of the art.

Autonomous Vehicle Architecture

Sensing

- Camera: Visual input for image-based perception (lanes, signs, lights, objects).

- Radar: Detects objects and measures their speed/distance (good in poor visibility).

- LIDAR: Laser-based sensor for 3D mapping and object detection.

- GPS: Provides global position.

- Others: Can include ultrasonic sensors, IMUs, etc.

Perception

- Detection & Classification: For a plethora of objects such as traffic lights, signs, pedestrians, vehicles etc.

- Tracking: Resolve occlusions and track objects over time.

- Free Space Detection: Detects drivable area.

- Localization: Determines the car’s precise position in the environment, using cameras, lidar and in general sensor fusion.

Planning

- Global Planning: High-level route to the destination.

- Prediction: Predicts the future actions of other objects (cars, pedestrians).

- Behavior Planning: Decides what the vehicle should do next (stop, yield, change lane, etc.) based on predictions and goals.

- Trajectory Planning: Computes a detailed path (trajectory) for the car to follow safely and smoothly.

Control

- PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) and MPC (Model Predictive Control): Algorithms to control the vehicle’s steering, throttle, and braking.

From Traditional to Modern AI Agents

In this course we will start with the basics of these subsystems but we will gradually infuse ideas from recent advances in large language models, vision-language models, and reinforcement learning to dramatically transform the capabilities of robotic systems. The ROSA demo above showcases how natural language understanding enables more intuitive human-robot interaction, while the autonomous vehicle architecture illustrates the sophisticated reasoning and planning required for real-world deployment. Key references: (Schmidhuber, 2015; Mirowski et al., 2016; Li et al., 2015)References

- Li, X., Li, L., Gao, J., He, X., Chen, J., et al. (2015). Recurrent Reinforcement Learning: A Hybrid Approach.

- Mirowski, P., Pascanu, R., Viola, F., Soyer, H., Ballard, A., et al. (2016). Learning to Navigate in Complex Environments.

- Schmidhuber, J. (2015). On Learning to Think: Algorithmic Information Theory for Novel Combinations of Reinforcement Learning Controllers and Recurrent Neural World Models.