If you are missing some algorithmic background, afraid not. There is a free and excellent book to help you with the background behind this chapter. Read Chapters 3 and 4 for the relevant background.

- Provided that the starting state is not the goal state, we add it to a priority queue called the frontier (also known as open list in the literature but we avoid using this term as it is implemented as a queue). The name frontier is synonymous to unexplored.

- We expand each state in our frontier, by applying the finite set of actions, generating a new list of states. We use a list that we call the explored set or closed list to remember each node (state) that we expanded.

- We then go over each newly generated state and before adding it to the frontier we check whether it has been explored before and in that case we discard it.

Forward-search approaches

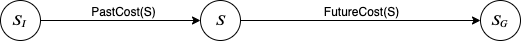

The only significant difference between various search algorithms is the specific priority function that implements in other words the function that retrieves a state from the list of states held in the priority queue for expansion.| Search | Queue Policy | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Depth-first search (DFS) | LIFO | Search frontier is driven by aggressive exploration of the transition model. The algorithm makes deep incursions into the graph and retreats only when it run out of nodes to visit. It does not result in finding the shortest path to the goal. |

| Breath-first search | FIFO | Search frontier is expanding uniformly like the propagation of waves when you drop a stone in water. It therefore visit vertices in increasing order of their distance from the starting point. |

| Dijkstra | Cost-to-Come or Past-Cost | |

| A-star | Cost-to-Go or Future-Cost |

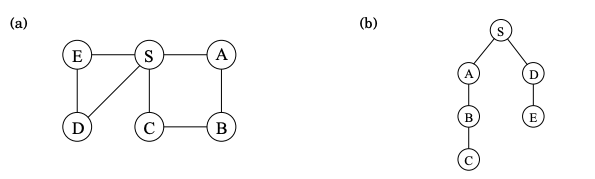

Depth-first search (DFS)

In undirected graphs, depth-first search answers the question: What parts of the graph are reachable from a given vertex. It also finds explicit paths to these vertices, summarized in its search tree as shown below.

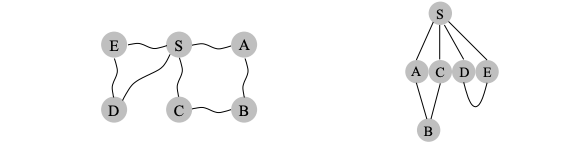

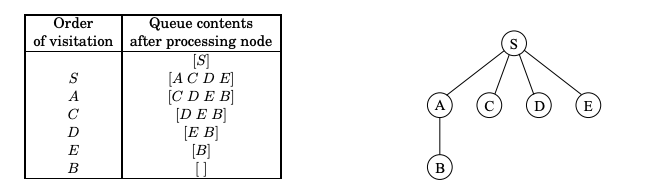

Breadth-first search (BFS)

In BFS the lifting of the starting state , partitions the graph into layers: itself (vertex at distance 0), the vertices at distance 1 from it, the vertices at distance 2 from it etc.

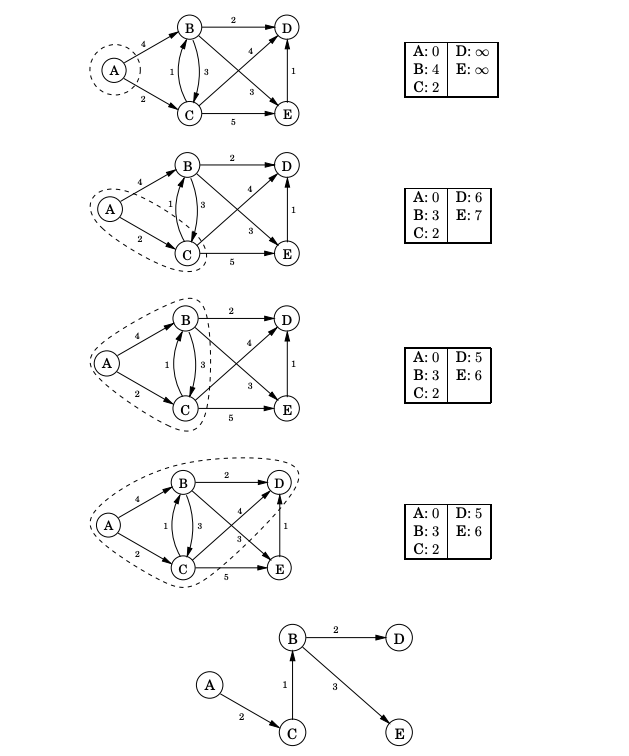

Dijkstra’s Algorithm

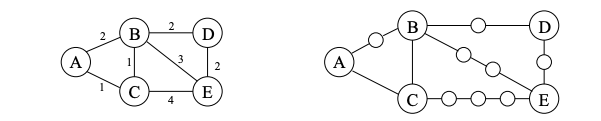

Breadth-first search finds shortest paths in any graph whose edges have unit length. Can we adapt it to a more general graph G = (V, E) whose edge lengths are positive integers? These lengths effectively represent the cost of traversing the edge. Here is a simple trick for converting G into something BFS can handle: break G’s long edges into unit-length pieces, by introducing “dummy” nodes as shown next.