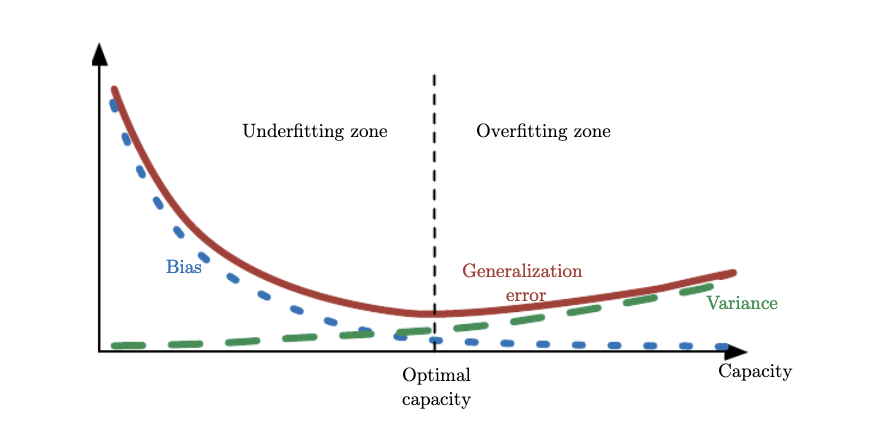

Bias and Variance Decomposition during the training process

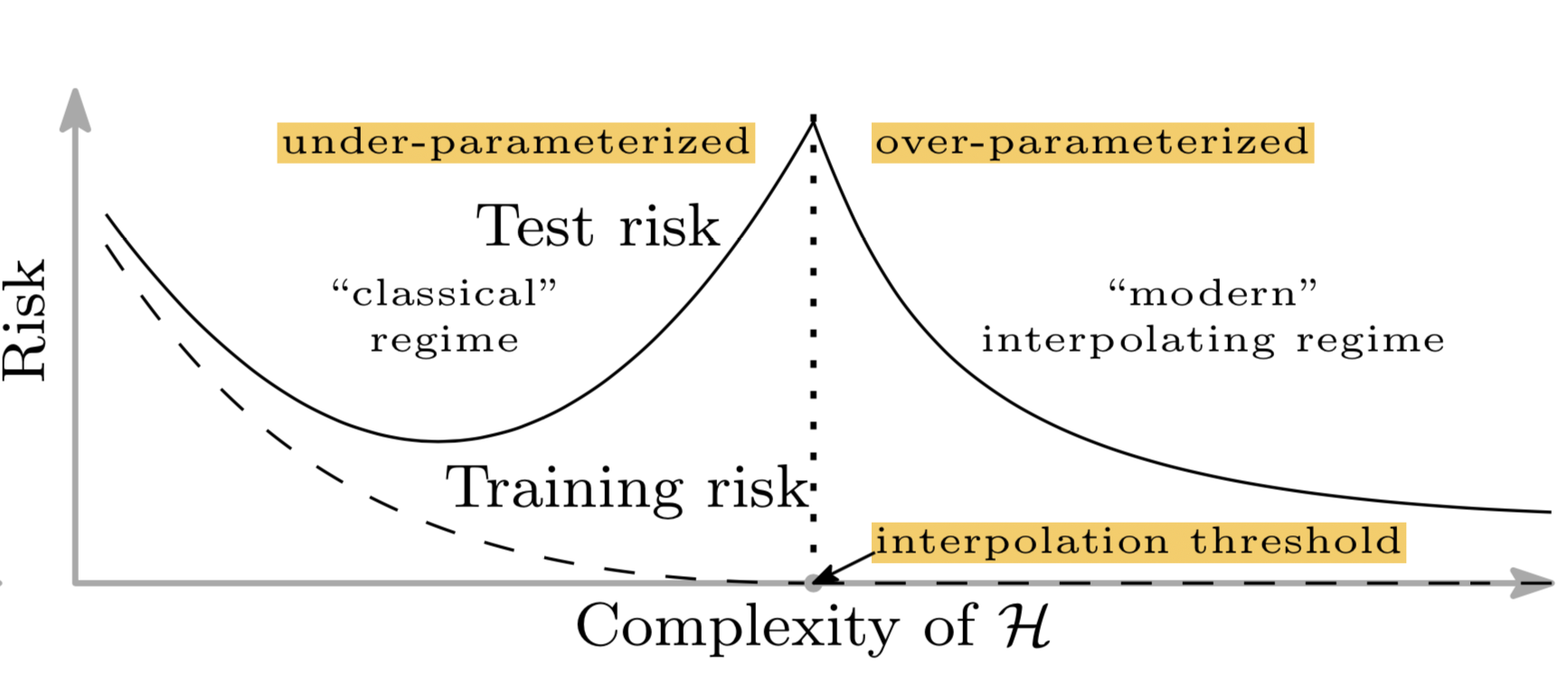

Apart from the composition of the generalization error for various model capacities, it is interesting to make some general comments regarding the decomposition of the generalization error (also known as empirical risk) during training. Early in training the bias is large because the predictor output is far from the target function. The variance is very small because the data has had little influence yet. Late in training the bias is small because the predictor has learned the underlying function. However if train for too long then the predictor will also have learned the noise specific to the dataset (overfitting). In such case the variance will be large because the noise varies between training and test datasets. Notably for deep learning models, the risk curve is exhibiting a pleasant property that indicates that despite the increase in capacity, the generalization error is increasing initially and then enters a regime where the error decreases avoiding overfitting as shown in the figure below.

References

- Bottou, L., Curtis, F., Nocedal, J. (2016). Optimization Methods for Large-Scale Machine Learning.

- Dauphin, Y., Pascanu, R., Gulcehre, C., Cho, K., Ganguli, S., et al. (2014). Identifying and attacking the saddle point problem in high-dimensional non-convex optimization.

- Goodfellow, I., Vinyals, O., Saxe, A. (2014). Qualitatively characterizing neural network optimization problems.

- Keskar, N., Mudigere, D., Nocedal, J., Smelyanskiy, M., Tang, P. (2016). On Large-Batch Training for Deep Learning: Generalization Gap and Sharp Minima.

- Keskar, N., Mudigere, D., Nocedal, J., Smelyanskiy, M., Tang, P. (2016). On Large-Batch Training for Deep Learning: Generalization Gap and Sharp Minima.